Once the country home of writer and socialist William Morris, Kelmscott Manor has a rich history. Here we delve into the heritage of what was once regarded as ‘heaven on earth’

Words Nancy Alsop

“With the arrogance of youth, I determined to do no less than to transform the world with beauty. If I have succeeded in some small way, if only in one small corner of the world, amongst the men and women I love, then I shall count myself blessed, and blessed, and blessed, and the work goes on.” So wrote William Morris, father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, writer, designer, arbiter of taste, socialist and pronouncer of universal design truths. If there exists an ultimate expression of that beauty he dedicated himself to transforming the world with, it is certainly to be found in a 17th-century farmstead on the upper River Thames, near Lechlade, Gloucestershire.

Kelmscott Manor

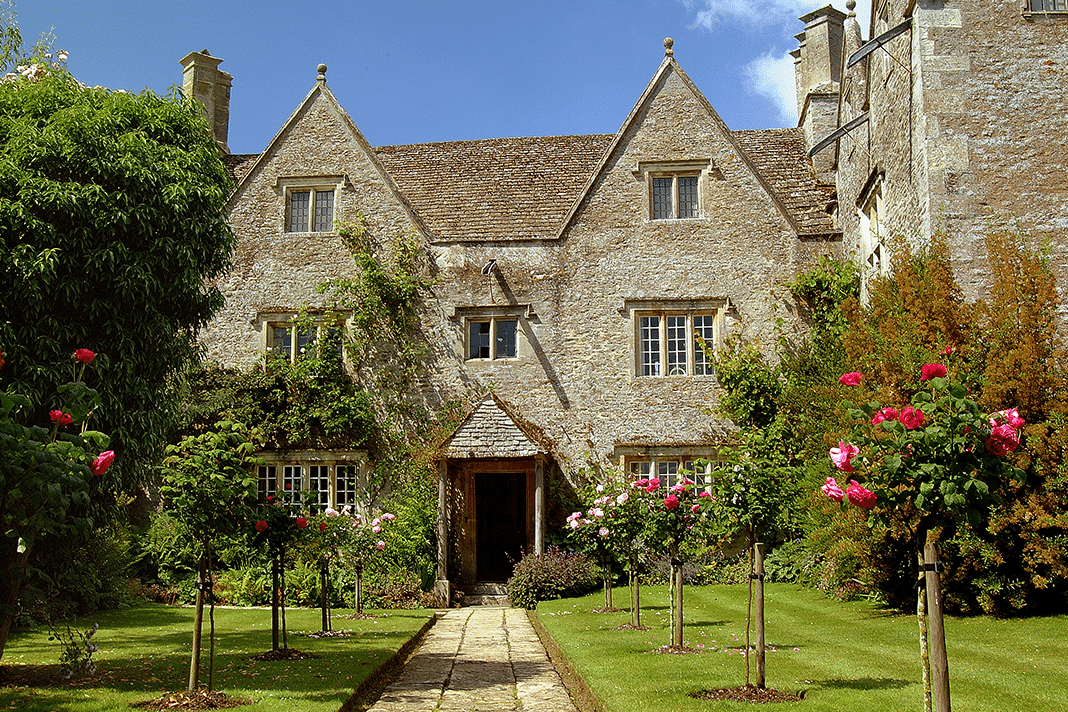

Kelmscott Manor – with its 12.5 hectares that house barns, stables and a dovecote, as well as the mellow limestone gabled house – was vigilantly and lovingly created as the physical manifestation of Morris’ ideals, along with those of the poet and Pre-Raphaelite painter, Gabriel Dante Rossetti with whom he leased the property in 1871. Together, in Kelmscott Manor, they created an idealised patch of England as they believed it should be.

Built in the 16thcentury with 17thcentury additions, its mullioned windows and local stone make Kelmscott an exemplar of English vernacular architecture of its time, and for Morris, its great appeal lay in the simple use of materials that make it appear to rise naturally from the soil on which it stands. Built by yeoman farmer Thomas Turner, Lower House, as it was then known, stayed in the Turner family for generations, until a more distant descendant – one Charles Hobbs – decided to rent it out and, in doing so, unknowingly sealed its stellar place in Arts and Crafts history.

Heaven on earth

Morris called it ‘heaven on earth’, a gushing yet sincere tribute to this place and its bucolic setting, surrounded as it is by trees and leading down to picturesque water meadows. (So enamoured was he that he also named his London residence on the banks of the Thames in Hammersmith after it, as well as establishing his own private press called Kelmscott Press.) He drew great inspiration from the unspoilt authenticity of the architecture and the organic nature of the garden; Kelmscott appears variously in his socialist novel, News from Nowhere, as well as in the background of Water Willow, a portrait of Morris’ wife Jane, painted by Rossetti. But if the house inspired the work, the relationship was certainly not unilateral.

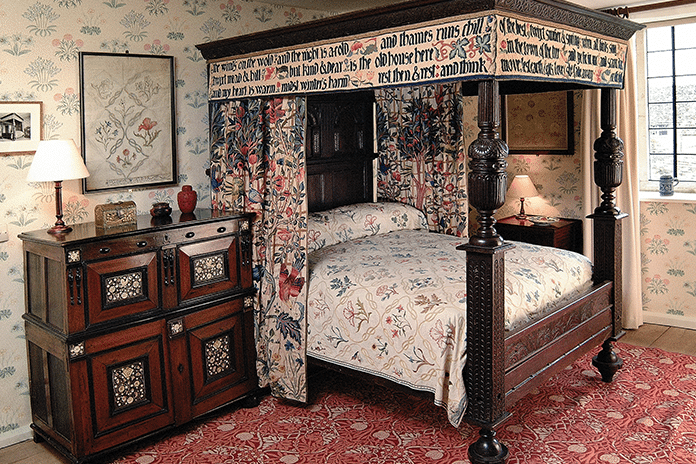

A tour of the manor today reveals a place where Morris’ transformative mark is indelible; the décor is rich with his famous textiles, as well as furniture of his own design, its heritage perfectly preserved thanks to his daughter May Morris bequeathing it to the solicitous care of Oxford University in 1938 in order that the public may see it and its legacy preserved.

A rich history

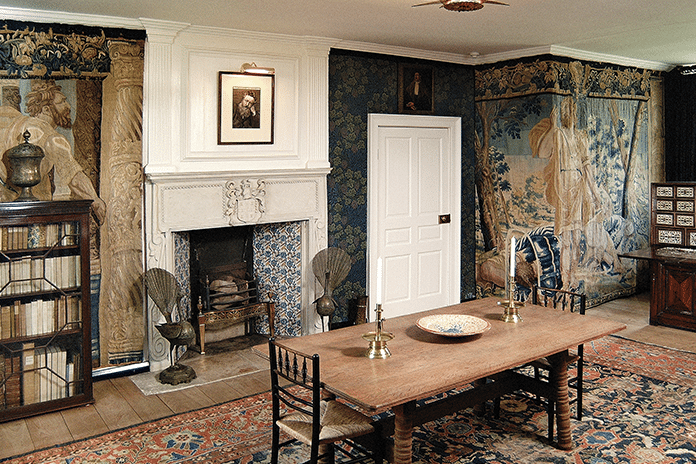

Laid out roughly in a T-shape, the collections at Kelmscott reveal a fascinatingly layered history. The hall features an original fireplace and several pieces of oak furniture that were in situ when the arts and crafts pioneer and Rossetti took up residence. Morris’ legacy can be seen here in the Strawberry Thief chintz with which the walls are hung, alongside hangings designed for Red House, his London home. Visitors should also note the tapestry in the Screens Passage, which shows a first attempt at his highly successful Cabbage and Vine tapestry.

But as ever, it is the marriage of the original house with Morris’ irresistible augmentations that make Kelmscott so achingly beautiful; the Panelled Room, for example, unites a 1670 fireplace, complete with Turner family crest, with an understated and plain white paint scheme. Throughout, decorative flourishes from Morris’ set abound; in the Green Room, there are a series of tiles designed by Edward Burne-Jones that illustrate Chaucer’s Legend of Goode Women; a satin and silk bed cover in Mrs Morris’ Bedroom by May Morris; a drawing in Morris’ bedroom by Charles Fairfax-Murray that depicts the great man on his deathbed – a sensitive sketch made at his bedside that was subsequently lost for many years before being restored to its place of origin; furniture by Ford Maddox Brown; and, of course, many works by Rossetti, as well as some of his effects, such as a rarely put away paint box on display in the Tapestry Room.

Later works

Many of the latter’s works were portraits and sketches of Jane Morris, including one of his finest works, Blue Silk Dress (1868). The frequency of her appearance in his work speaks of more than just her role as his long-time muse; William Morris’ wife was also Rossetti’s lover – a passion that intensified during their time at Kelmscott, but one that had been a long time simmering. Jane Burden, as she was before her marriage, proved a prolific inspiration for the Pre-Raphaelites. The daughter of a stableman in Oxford, Rossetti had first spied her in the audience at the theatre and immediately asked her to pose for him. She demurred, but was later persuaded to model by Edward Burne-Jones – and thus the pre-eminent star muse of a movement was born. When Morris later began to paint her as Queen Guinevere from Arthurian legend, he wrote on the back of a canvas: “I cannot paint you, but I love you.” Despite agreeing to marry him, it is thought that Burden’s heart had always belonged to Rossetti, himself married to another of his muses, Elizabeth Siddal, at the time. Their affair began in 1865 after Siddal’s death; the tenancy of Kelmscott was taken, in no small part, to keep their affair, which continued until Rossetti’s death, private and away from prying eyes and gossiping mouths.

And yet, Morris – aware of and distressed by the affair – undoubtedly loved Kelmscott Manor despite the personal pain with which it was bound up for him. It was, perhaps, precisely because he could lose himself in his perfectly simple garden, which eschewed fancy flowers in favour of simple cottage garden blooms, planted for bees to draw their nectar from that Kelmscott was such a utopia. Here he tended and then wrote about his snowdrops, his daphne, and his hepatica, doubtless drawing inspiration from them – and the birds who frequented his garden paradise – in turn for his own work. There can be no greater paradigm of his dictum to “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful” than Kelmscott Manor.